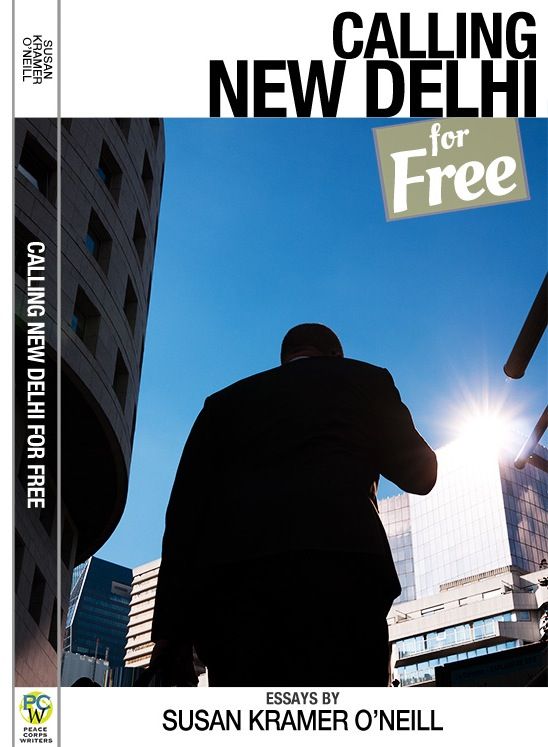

Calling

New Delhi for Free (and

other ephemeral truths of the 21st century)

Technology first rocked our world when a lightning bolt zapped a bush at the entrance to a cave, and First Man crawled out and stuck his hand into the mystical blaze. Centuries later (just how many seems to depend on your religious orientation), we still find technology fascinating, mysterious, distracting, vital and Wow! Shiny!—and it still fries our grasping, hapless human hands, not to mention our grasping, hapless human brains.

Order it here.

No

Questions Asked

I stood mired in

WalMart amid televisions tuned to Dr. Phil. Hundreds

of Dr. Phils.

Thousands.

“Breathe,”

I told myself.

WalMart

overwhelms me. I’m drowning in a great wave pool,

buffeted by tsunamis

of

gleaming inventory—advancing, retreating, pulling me

to buy. When I

surface

long enough to remember what I came for, when at last

I grasp my

particular

pulsating silver siren delight, it turns to pressboard

and veneer in my

hands.

I

never go to WalMart.

But

I had flown in the night before, from Massachusetts to

Indiana, to

visit Ma,

and if you want to buy a television in Indiana, you go

to WalMart.

I

held my breath, plunged my hand into a stack of boxes

and grabbed a

20-inch

flatscreen TV.

Gotcha.

Once

the set and I were safely in my rented car, I mopped

my brow and

congratulated

myself. I had survived. I had gotten a good deal. I

would reward myself

with a

glass of wine tonight.

But

first, I had to drive from Fort Wayne, where I was

staying, to the tiny

town of

Avilla, 30 miles away, to deliver my prize to Ma.

Ma’s

got Alzheimers, but she’s doing well in her new

Assisted Living

apartment. The

Avilla facility came with cable access, and my sister

Mo had told me

that Ma’s

14-inch TV, a relic from her and our

late dad’s

house, was too low-tech to work with it. The new TV

would be my

housewarming

gift.

I

carried the box into Ma’s spacious studio and gave

her a hug. Ma has become a bit deaf, and her little old

TV was blaring

Dr.

Phil’s show.

She

glanced at the box. “I don’t want that thing. I

get three Fort Wayne channels real clear here.”

I

wrestled the set from the box. “Trust me—you’ll love

it. It’s bigger. And it’s got closed captioning, so you

won’t have to

play it

so loud.”

“What?”

“Closed

captioning.”

“What?”

“THOSE

WORDS THAT MOVE ACROSS THE BOTTOM OF THE

SCREEN,” I shouted. “With this bigger TV, you could

actually read

them.” I

turned off her old TV; the quiet was instant, cottony. I

put the little

set in

the closet and placed the flatscreen on the end table

she used as a

platform.

“Watch it for a couple days,” I said. “If you decide you

don’t want it,

I’ll

take it back.”

“You

can’t take something back just because I don’t

like it.”

“You can

take anything back to WalMart,” I assured

her, hoping I’d never have to find out if that was true.

“No questions

asked.”

The

facility handyman was off for the day, so the

cleaning lady helped me connect the flatscreen to the

cable box. Ma

said, “I

hate all those wires sticking out. If I had my dresser

from the house,

I could

put it on that, and they wouldn’t show.”

She was

referring to the house she no longer owned.

This would segue into an argument over the way my sister

Mo had

parceled out

Ma’s furniture to family members. Ma had given full

permission, but

couldn’t

remember doing so.

I

avoided the topic of the dresser; you can’t win an

argument with someone who has Alzheimers. The cleaning

lady and I

rearranged

the cables. “They make special furniture to hide TV

wires,” I said.

“What?”

“ENTERTAINMENT

CENTERS, Ma,” I said. “You need an

entertainment center for your new TV.”

The

cleaning lady and I tried to program the flatscreen, but

we couldn’t

make it

work. The cleaning lady left to go clean something. I

pushed aside the

cable

box and plugged the flatscreen straight into the wall,

where Ma’s old

set had

been connected. Let the handyman hook it up tomorrow.

Until then, she

could

watch her three stations on a nice big screen.

Ma

frowned at Dr. Phil. “It’s so dark.”

I

brightened the picture. The doctor’s teeth gleamed like

angel wings.

“I

like my TV better.”

I

disconnected the flatscreen and reconnected her old set

to the wall. I

turned

it on. She cranked it up past Deafening.

While we

played her favorite card game, Spite &

Malice, I entreated her over Dr. Phil’s stentorian

platitudes—when is

the man not on

TV?—to give the flatscreen another chance tomorrow,

after the handyman

got it connected. If she wasn’t pleased, I promised,

I’d return it to

WalMart.

“They

won’t take it back just because of that.”

“No

questions asked,” I assured her. “And I’ll find

you an entertainment center.”

She

threw the winning card on the table as Dr. Phil’s

audience applauded, vibrating the room. “Where would you

find that?”

Where,

indeed.

That evening, I sat in a Fort Wayne

Pizzeria Uno and

stared over my wineglass, across the parking lot, at

WalMart.

Sooner

or later, everybody learns to love me, the

boxy building told me.

“Right,”

I said.

The

waitress halted at my table. “What?” she said.

----

I

stopped at WalMart the next morning. A different

WalMart, closer to Ma’s facility. In Indiana, every

major parking lot

has a

WalMart. I swam

clench-throated through shoals of

glittering inventory until I found an entertainment

center. It was four

feet

long, ridiculously heavy, and came in a flat carton.

The WalMart

greeter and I

shoehorned it into the back

seat of my rented car, then he went off for hernia

repair.

I

borrowed the Avilla facility’s hand-truck and wheeled

the carton down

to Ma’s

apartment.

Dr.

Phil rumbled from her old TV. “Voila!”

I said.

“One

entertainment center. Some assembly required.”

The

handyman arrived and set up the new TV. It still

wouldn’t work. It was connected to the cable box, but it

still received

only

Fort Wayne’s three channels. He promised he would call

the facility’s

electronics wizard the next day. He programmed the

closed captioning

and left.

“The

words move too fast,” Ma said. I de-programmed

the closed captioning.

I worked

for three hours assembling the entertainment

center, until I discovered I was missing a tiny

wedge-shaped piece of

plastic.

It was the sole, vital connection between two beveled

strips of

veneered

pressboard, and was not in the hermetically-sealed

accessory bag.

I told

Ma I had to drive back to WalMart for the

piece.

She

glanced up from a thundering Dr. Phil. She spoke.

“What?”

I said.

“THAT TV

IS TOO DARK.”

----

At WalMart, the courtesy woman and I

dragged

another

boxed entertainment center from the shelf. I ripped open

its

hermetically-sealed

accessory bag and picked out its vital plastic wedge.

I sped

ten miles back to Ma’s place.

My

sister Mo was there, arranging Ma’s meds. Dr. Phil

boomed from the new TV. Ma said, “That TV’s been turning

itself off.”

Mo

shrugged; she hadn’t witnessed it. I tightened the

cables.

Mo held

the back of the entertainment center and I

screwed it to the sides. Suddenly, the room fell silent.

The new

TV had turned itself off.

“Must be

the cable box,” I said. I disconnected the

box, reconnected the flatscreen directly to the wall,

and turned it

on. Dr.

Phil roared back to life.

We

were hanging the entertainment center’s doors when the

TV died again.

“Hmm,” I

said. “It’s not the box.” I unplugged it and connected

Ma’s old set to

the

wall.

Ma

pumped up the volume. “I told you I liked my TV better.”

Two

hours later, Mo and I finished assembling the

entertainment center. It

was

big, bigger even than the disputed dresser Ma no longer

owned. It would

have

been perfect to hide the new flatscreen’s wires and

cables, if the new

flatscreen had worked. Instead, Ma’s TV sat on top, a

raving peanut on

a vast

plain of pressboard and veneer.

I

gave her a quick hug and grabbed the dead flatscreen.

“They

won’t take it back,” Ma said.

“WalMart

takes anything back, no questions asked,” Mo told her.

----

And

that very night, they did.

I

stuffed the receipt in my pocket, wrenched myself from

the swirling,

shining

multiplicity of Dr. Phils, and dogpaddled out the door.

I

staggered to Pizzeria Uno, where I ordered a glass of

wine.

I

stared out the window, over my wineglass, over the

parking lot. At

WalMart.

WalMart

stared back at me. Triumphant. Sooner

or later—

“WHAT?!”

I said.